Just as all of us

parents were confident about our children’s progress through the first grade,

the teachers requested that we buy display panels for an exhibit called “The

Story of Me.” Our first-grader is now a

teenager, but the project was so detailed that I remember most of its

complications. “The Story of Me” was intended as a joint parent-child project

that included pictures of a variety of family members at different stages of

life, as well as pets, family weddings, homes and apartments, holidays, and

trips away. If possible, all photos were to be fully identified and dated, but

otherwise everything relevant was acceptable. This last provision gave ample opportunity

for omissions, strategic and otherwise, which could be papered over with yet more

photographs. I began to feel I knew what President Nixon might have been

thinking during the Watergate cover-up, and not because of his Quaker

connections.

As it happened, the

issue of religion came up early. There are only around 1200 Friends in Canada,

and as far as I know, we are the only Quaker family connected with that school,

at least for any length of time. Our first-grader wanted wedding photos, and

the ones she chose required a bit of explanation for those unfamiliar with

Quaker marriage customs. Well, I shrugged, “Some parents will bring in pictures

of themselves snuggling with their newborns in the neonatal ward, so I guess

sex is already by implication part of the story. If we bring up religion and,

by extension, politics, then among the lot of us we will have hit the trifecta

of impermissible discussion topics.”

If only the project

had ended there.... The one relevant photo that seemed to have gone missing was

the sole extant family picture of the place where my husband and I had met:

Jesus Lane Friends Meeting House in Cambridge, England. (At least some of my

photos from that period turned up years later in my parents’ basement next to a

box of craft supplies, the day before the house was sold, so we may have it

once again, although I haven’t checked.) Of course, that was the one our

daughter most wanted, and it had to be the same size as the other pictures. No

matter how I tried, I couldn’t get the Meeting website to download and print. (Computers

weren’t then what they are now.) We all looked at each other: would a map of

Cambridge do? No. How about some other building in the city —let’s say the most

impressive one we could find — King’s College Chapel, maybe? That would hardly reflect

the Quaker testimony of integrity, now, would it?!

I eventually got the

Meeting website to print. By some miracle the photo was the right size. (I

vaguely remember e-mailing the warden as to whether it was acceptable to use it.)

The pictures and captions were glued on in the right spots. Our project, like

the others, received a warm reception.

At that point I just

wished that the members of the older generation of Jesus Lane Meeting whom we

had known when we were Young Friends were still alive, as I would have liked to

have returned to them with our daughter in tow. I am indebted to a number of

them in different ways. Some of these Friends will come up in other posts; other

reminiscences are more personal in nature. The Friend whose name came to mind that

day, though, was the redoubtable Anna Bidder. Friend Anna was known to the

academic community as a biologist, an expert on cephalopods. She was a

co-founder and the first president of Lucy Cavendish College at the University

of Cambridge. She was also familiar in Quaker and in some non-Quaker circles as

one of the co-authors of the pamphlet Towards

a Quaker View of Sex, to which she contributed her biological expertise. But

to Young Friends in Jesus Lane Meeting she was most familiar in two capacities:

as a long-serving Elder and as the indefatigable hostess of Young Friends’

gatherings on Sunday evenings in her home on the south side of Cambridge.

We would turn up

punctually at seven p.m. and find her living room blue with cigarette smoke.

(She lived to be ninety-eight, and I have no idea if she ever did quit

smoking.) At around eleven, she would wave us off with the words, “I love you

all very much, but I have a meeting tomorrow at eight a.m.” Sometimes one or

another of us would visit alone. On one such occasion she made me tea, and then

found out to her horror that my all-American method was rather primitive — tea

bags. If someone disliked having the tea leaves steep in the pot indefinitely, one

could always make a smaller pot and use a tea strainer. To drive the point

home, she fished a small vegetable strainer out of the drawer. The next time I

had a hostess gift, since I figured there would be other American Young Friends

along sooner or later.

One evening I arrived

just before the other Young Friends, which gave me the opportunity to ask how

she became involved with Quakers. “It’s quite simple, my dear. I am a natural

pacifist. At the end of World War I, I was one of two million excess women in

England.” She continued with a list of the brothers and cousins of her school

friends, almost all of whom were second lieutenants killed in that war. Her

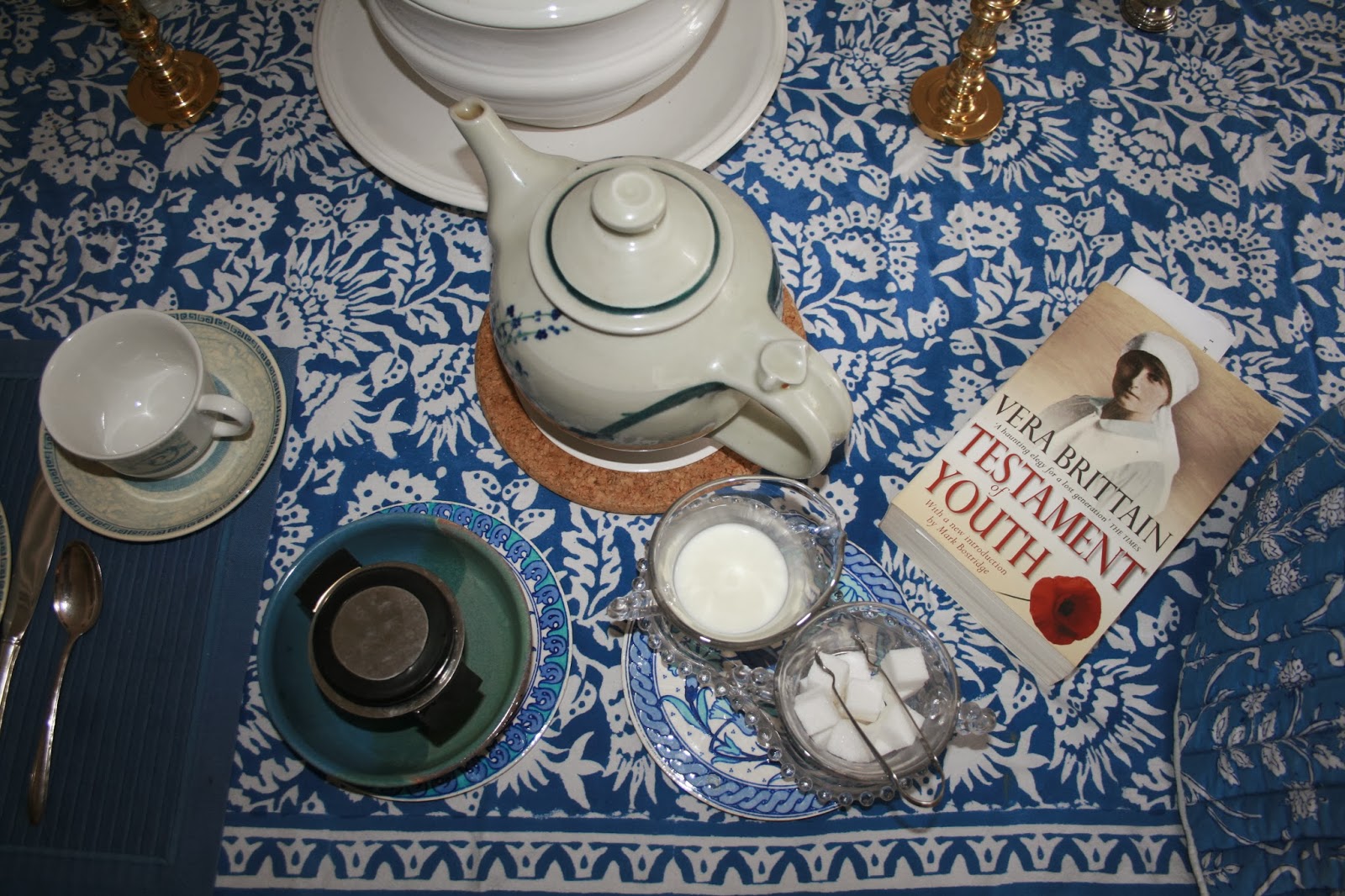

answer was a jewel-box version of Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth, which was always on display among the red

poppies before Remembrance Sunday at Heffers bookstore. I could picture her

going through childhood photographs in her head.

I sat there in shame.

Here we all were, Young Friends flirting and joking in the home of someone who

had made her place available to us precisely because these were the pleasures

she had been denied. This decision on Anna Bidder’s part was consistent with

her work to help establish Lucy Cavendish College, which was established for

women students whose educations had been disrupted by domestic responsibilities.

Such responsibilities usually consisted of the husbands and children she did

not have.

Knowing how Anna felt

about “excess women,” I have wondered what she would have thought of the

“excess men” in some parts of the world, where the ratio of boys to girls has

now been skewed for the better part of a generation. It does not take much

imagination to conjecture a response. An unnatural ratio of either sex results

by necessity from violence and tears. Those lucky enough to live in an

environment with roughly equal numbers of people of each gender ought to think

whether our own good fortune should make us “natural pacifists” as well. And,

as we approach the centenary of the outbreak of World War I, it is incumbent

upon all of us to ensure that our children, as they look back on photographs of

their first-grade classmates in the years to come, do not have to say which

ones were gunned down, or gassed, or bombed, or otherwise left to perish in despair.

No comments:

Post a Comment